S& P 500 hits all time highs U.S.-Japan trade deal optimism

The Asset Manager’s Bid for the Soon-To-Be Bottleneck in the AI Boom

In a market fixated on one industry, one development, and one company in particular, it can be easy to lose track of the big picture. The past two years' hysteria around microchips, artificial intelligence, and cryptocurrencies has left many investors wide open and exposed to potential hiccups in the seemingly unstoppable tech hegemony. Some—like BlackRock (NYSE: BLK)—however, are beginning to notice the auxiliary sectors that make it possible – namely power. Their recent acquisition of one of the largest infrastructure companies on the planet—Global Infrastructure Partners—is their modern equivalent of selling shovels in a gold rush. The global electrical grid becomes a talking point when its until-recently-believed-abundant capacity is put in question.

The Setup

History is filled with examples of large financial institutions such as investment banks, asset managers, and hedge funds getting into specific fields before their mass appeal and potential for gains is revealed to the rest of the investment world.

And that's no surprise considering these companies' main goal is to make smart investments that generate profits. It's only natural that they would catch a whiff of tacit opportunities before others do.

In January of 2024, BlackRock—the largest investment firm in terms of assets under management—reported their acquisition of the largest infrastructure manager in the States and globally – Global Infrastructure Partners.

This marked the biggest purchase by the titan in more than a decade, priced at $3 billion in cash and an additional 12 million shares of BlackRock stock. It comes at a time when the giant is probing for alternative investment opportunities, particularly in the fields of private equity, private debt, and infrastructure.

This acquisition is the farthest from coincidental. Although infrastructure has long been a fringe investment arena, it is coming up more and more into the public consciousness. Recent developments in technology have gradually increased the power consumption for processing-power heavy data centers used for activities such as cryptocurrency mining, AI training, and cloud computing.

Chips And Tokens

Blockchain technology opened up a new avenue where computer processing power can be used – in the solving of complex mathematical puzzles to verify transactions. This is known as cryptocurrency mining, and for the blockchains that use the Proof-of-Work model, this is the only way that users can obtain the blockchain's token.

Bitcoin was invented partly with the idea of being a scarce digital currency, meaning it would theoretically not suffer from devaluation due to more of it constantly being produced. It was hard-wired to have a maximum number of its tokens ever in existence with their creation halving every four years or so.

Those problems that the computers on the network must solve become harder while the rewards they yield become lower, as a way to balance this micro-economy. In the dawn of crypto mining, you could easily use your own personal computer to pool your computational power with other people and get sizeable rewards for it.

However, as time went on, the idea of a regular computer being able to do any kind of meaningful work became laughable. Hundreds of 'coin farms' were created across the globe that connect hundreds or thousands of machines designed to solve those mathematical problems – essentially creating economies of scale in that segment.

That phenomenon was talked about numerous times over the years, especially in relation to electricity. This is because such huge hardware facilities can use a lot of power. It was necessary to find the cheapest power available, which caused many Chinese 'farmers' to flock to Texas after their government banned cryptocurrencies outright.

Cryptocurrency mining is estimated to account for between 0.6% and 2.3% of the total United States electricity consumption annually, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

The other growing electric power consumer in the world are data centers. Those are—again—computer facilities that can house thousands of machines used primarily for cloud data storage and cloud computing. They enable big tech clients to outsource the computing power to a facility that has the capacity to handle their workload without having to invest in the costly infrastructure themselves.

This segment of the economy has grown exponentially over the past couple of years. Nvidia (NASDAQ:NVDA) (NASDAQ: NVDA) is the de facto monopolist in the chip market at the moment. They're responsible for developing the cutting-edge microprocessors used in training AI models.

Generative AI such as OpenAI's ChatGPT, Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT)'s (NASDAQ: MSFT) Copilot, and Google's (NASDAQ: GOOG) Gemini require immense amounts of computational power to train those models with as much data as possible as quickly as possible. The only reason they have put such a premium on this sci-fi tech is because it has actual practical applications.

The AI business is good. It is supplementing work on an organizational and individual level, so the demand for it shows no signs of decreasing, while supply is trying to keep up. That rapid spike in computational demand had a proportionately large effect on power demand. Data centers consumed roughly 460TWh of power in 2022. For reference, this is about 2% of the world's total demand, according to the International Energy Agency.

Strategic Positioning

While cryptocurrency mining has only moderately affected its power demand, the megacap tech companies like Meta (NASDAQ:META) (NASDAQ: META), Microsoft, Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL), and Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN) (NASDAQ: AMZN) have doubled theirs between 2017 and 2021. The combined usage of data centers, artificial intelligence, and cryptocurrencies is forecast to double by 2026 in the high case scenario. That would be the equivalent of adding one more Germany to the world's consumption.

These demand shocks will not only put pressure on the production of electric power but also on its transportation over an already encumbered network. There are two facets to the electric infrastructure that are of great importance and can pose challenges in the coming years.

The first one is the increased strain on grids that are not designed to handle the load of data center clusters which tend to be localized rather than geographically dispersed. This has historically created complications for some areas and has led to the creation of incentives for large power consumers to curb their use during peak hours.

In addition, BlackRock themselves emphasize the need for public-private partnerships in the domain of infrastructure development. Governments alone would find it difficult to finance such operations—BlackRock argues—due to strain from their 'large deficits'. These developments can become even more difficult due to high borrowing costs in a high-interest environment.

BlackRock's plan is to get on the ground floor of the lucrative infrastructure market before governments and companies realize one of their most profitable industries—and their whole economies for that matter—could be bottlenecked by power supply.

BlackRock commands some $10 trillion worth of assets currently. These are substantial holdings that have the power to sway entire markets. Their acquisition raises some questions about the future of the electric grid and about infrastructure in general.

If governments become reliant on the private sector for grid expansion beyond their capabilities, what power might that put into the hands of colossal financial institutions? Granted, they won't control the whole train but how much can they get away with if they have laid down the tracks?

In an age of full transition to digitalization, how much can the ones who own the means of power creation and transmission manipulate the most valuable resource's price? We need only look to petroleum to understand how an oligopoly might operate in an uncontested market space.

BlackRock is estimating this deal is going to benefit its earnings per share in the twelve months after it’s closed. This positive guidance is supported by the likes of Morgan Stanley, who forecast a potential price tag per share of $1,025 in the following fifty-two weeks, according to TipRanks. This doesn't seem at all unattainable considering their fundamentals. Now let's take a look at their technicals.

Technical Analysis of BlackRock

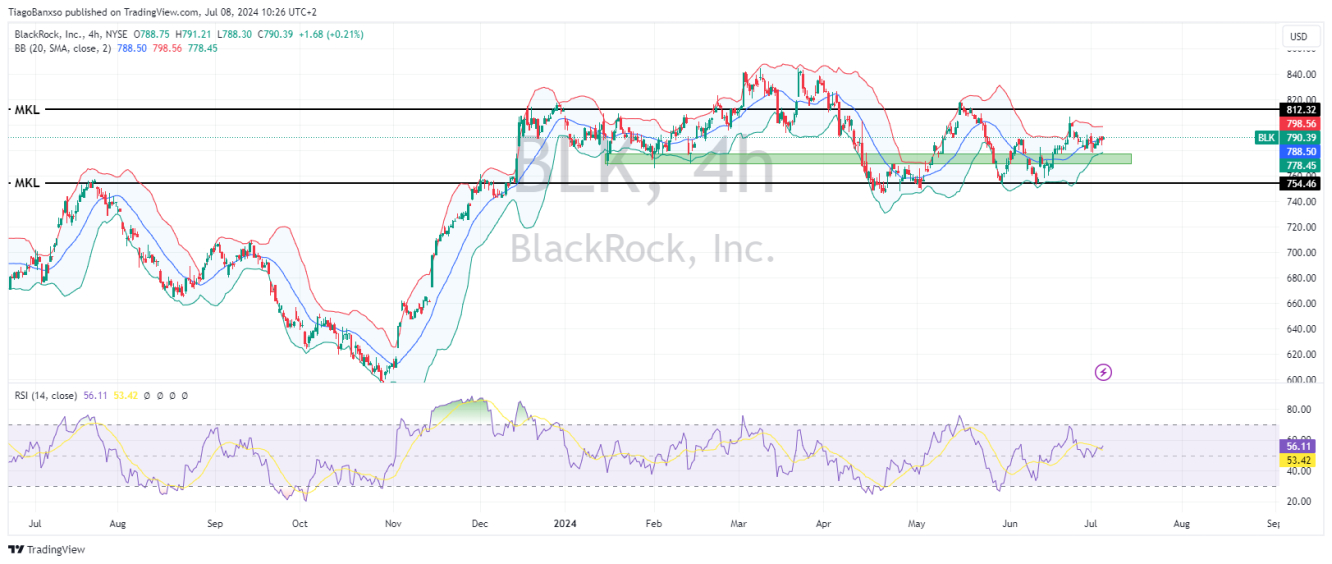

Price Range

- The stock was trading in the range of $777 - $791 during the week starting July 1st.

Key Levels

- $812 is Monthly Key Level and a resistance.

- $754 is a current support that was historically a resistance in 2020 and in 2022.

- The price has been oscillating between $812 and $754 for the past 203 days (about six and a half months), indicating a likely continuation of this range-bound behavior in the near term.

Fair Value Gap

- Fair Value Range between $770 and $777.

- A recent fair value gap can be observed within the range when a disbalance was created due to increased buying activity. It might reflect a disagreement between buyers and sellers on the fair value of the stock and the price could potentially retrace back to that area.

Relative Strength Index (RSI)

- Current RSI Level: Oscillating around 50

- The RSI went into the overbought zone mid-May and has since only touched that boundary. Currently, it's printing near the midpoint value of 50, indicating a neutral momentum.

Upcoming Earnings Report

- The upcoming Q2 Earnings report on July 15, 2024 could cause higher volatility and potentially lead to a breakout from the current range between $812 and $754.

Bollinger Bands

- Currently, the price is currently at the middle band, indicating a neutral stance where the 20-day Simple Moving Average (SMA) acts as a support and resistance level.

- The upper and lower Bollinger Bands are narrowing, suggesting a period of consolidation. This tightening often precedes a breakout.

- Given the narrowing bands, a breakout can be anticipated. The breakout could potentially propel the price towards the $812 resistance level.

Which stock should you buy in your very next trade?

With valuations skyrocketing in 2024, many investors are uneasy putting more money into stocks. Unsure where to invest next? Get access to our proven portfolios and discover high-potential opportunities.

In 2024 alone, ProPicks AI identified 2 stocks that surged over 150%, 4 additional stocks that leaped over 30%, and 3 more that climbed over 25%. That's an impressive track record.

With portfolios tailored for Dow stocks, S&P stocks, Tech stocks, and Mid Cap stocks, you can explore various wealth-building strategies.